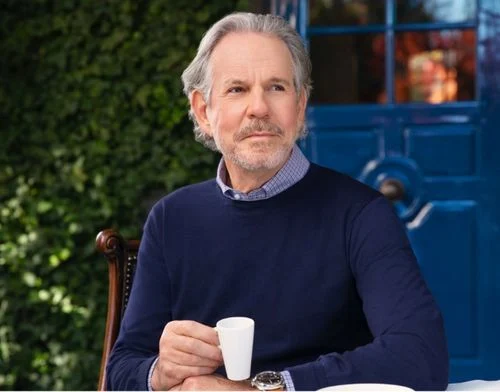

Thomas

Keller

America's Most Decorated Chef

T here’s a quiet intensity to Chef Thomas Keller that is most evident in the kitchen. You can see the glow in his eyes, feel the full force of his focus the moment his chef’s whites are buttoned up. His every movement is filled with purpose as his hands deftly rotate between tools, plates, ingredients.

And Chef Keller speaks with reverence for the physical activity of cooking, noting the importance of cherishing each step along the journey of a culinary career. As you progress towards becoming a chef, or chef/owner, while you are still “developing recipes and repertoire,” your role begins to separate from the motions that define your early career. It becomes about guiding and promoting trust in your team. You pass the torch, in some ways gradually, in some ways dramatically. You’re now there to make sure the flame is still burning brightly.

Keller is still very much present in his kitchens, standing in at a station when necessary, even washing dishes. As much as he retains a fondness for “dicing those vegetables, making the brunoises, putting that piece of fish in the sauté pan,” he’s aware that his responsibility now is to something more complex. As he describes it, he’s the general manager of a sports franchise rather than its star player and captain.

In sport, as in food, he considers himself a traditionalist. While he revels in the relaxation that he finds on the golf course, he especially identifies with the subtleties of the game.

“The way you walk up to a green, the way you mark your ball,” he says. “There’s a responsibility to graciousness toward others on a golf course.”

Golf is a time for private focus and commitment—a meditation. Combining his two passions, he hosts a charity event each year at the local Silverado Resort to benefit the Culinary Institute of America. There’s even a putting green in the gardens across the street from the restaurant, a surprise gift from his staff several years ago.

The gardens, a refuge for guests and the Yountville community, are a pivotal source of fresh ingredients for Keller’s local restaurants. A dedicated staff works in tandem with the chefs to plan future plantings and develop daily menus. It’s one of the ways he hopes to further foster an essential respect for ingredients, both for the in-house produce and what’s sourced from their hundreds of specialized purveyors.

Keller is also mindful that wine is the reason many of his guests visit The French Laundry in Napa Valley. The wine program here certainly reflects a celebration of its culture, with more than 2,500 different selections on the list curated by head sommelier, Andrew Adelson. Modicum, their proprietary bottling, connects vine to restaurant. It started as an idea from Keller’s life partner, Laura Cunningham, the VP of Branding and Creative Development for the collective group of restaurants and consumer product division. Keller and Cunningham work with their sommeliers and local vineyard owners to create new releases each vintage.

“We learn as we go. We evolve as we go. What we want to do is nourish our

guests, and in the same way, nourish ourselves.”

And for Keller, the food has to respect the presence of wines as well, especially the signature wines of the region.

“Our flavor profiles have to be of a traditional sense so that people can not only enjoy the food but enjoy wine with food. We can’t go off the edge with different flavor profiles that don’t really marry well with wine, ” he says.

With Chef Keller, everything comes back to the team. It’s always “our restaurant,” never “my restaurant.” And developing his teams all starts with the dishwashers, whom he prefers to refer to with the more respectful “porter” moniker. It’s the position where he started his own path toward becoming a chef.

He confesses that one of the great planning missteps in his career was in not bringing his head porter at The French Laundry to train the new staff when opening Per Se, the sister restaurant in New York that now also holds three Michelin stars.

“We have such an extensive array of plates, china, ceramics, glass. It’s extraordinary,” he says. “The new porter team at Per Se was overwhelmed the first night. They just didn’t know what to do with all these things.” He promptly got on the phone to Juan Venegas, his then-porter at The French Laundry, and flew him out to New York to help guide the new staff.

This passion for detail, for perfecting every process, and the idea of respect flow throughout his teams and across all his restaurants, which exchange ideas on a daily basis.

At the middle of it all is the station Keller cites as the “heart and soul” of the restaurant: the Pass. Here, plated dishes are finished and passed from the kitchen to the service team, who present them tableside. Its importance is paramount when the emphasis is on the experience as much as the meal itself. Precise timing and communication shape the level of that experience, and this is center stage for execution.

Interestingly enough, Chef Keller notes that the team members who head the station, the expeditors, are often some of the youngest at the restaurant, currently two women promoted from the running team.

“Without her, or him, nothing really happens. That person is the one who’s keeping the tempo going, exchanging the information, directing to the chef, to the dining room,” he says.

Identifying young talent with the unique mindset to succeed in this pivotal position is a sign of the trust he shares with his team, and commitment to the thorough mentorship he identifies as such an important pillar.

“Our job is to give each of us—even the youngest people in our restaurant—the confidence and the courage to stand up for themselves,” he says. “If you hire the right person, if you give them the proper training, and you mentor them correctly, what happens to that person? That person becomes better than you. So if they’re not better than you, you have not done your job very well. And that’s kind of the benchmark for us.”

Keller and his team have won just about everything there is to win in the world of fine dining, raising the bar for what’s possible for American chefs, and the standards for the culinary profession as a whole. Alongside, Cunningham has been instrumental in crafting an elegant yet approachable service style over more than 20 years that exemplifies the character of the restaurants and continues to influence the direction of hospitality today.

Along with other contemporaries Keller is quick to name—Daniel Boulud, Jean-Georges Vongerichten, Jonathan Waxman, Alfred Portale, Larry Forgione, Charlie Trotter—his own generation elevated the idea of what it was to be a chef in this country, at the same time proving that America was capable of competing with any of the masters from the Old World. Further than that, their high-level restaurants became living proof that a job in the culinary world could be a space to pursue a viable, fulfilling career.

He also feels especially indebted to Sally and Don Schmitt, who opened The French Laundry in 1978 and sold to Keller in 1994. Nods to the history, including the permanence of the iconic blue door, are ever present.

Surrounded by adoring guests during the 25th anniversary celebrations at the restaurant in 2019, most chefs would have been simply enjoying themselves. But Keller felt uneasy.

“I realized that I was celebrating 25 years of Thomas Keller at The French Laundry. And that was wrong,” he says. “The French Laundry was 17 years old when I came on the scene. Out of respect for the restaurant, we have to celebrate the restaurant’s anniversary, not Thomas Keller at The French Laundry.”

Keller has a way of making everything sound so simple. His embodiment of effortlessness will put you in a trance. When you dine here, you do not feel the behind-the-scenes intensity. The procession of flavors, the service team anticipating your every need—it all washes over you like a steady, gentle wave.

And what of the food itself?

For Keller, it starts by generating a “response of desire” through visual presentation, even if crafting aesthetically ambitious food comes with a responsibility to live up to the expectations it sets. “The worst thing you can do is present somebody something that looks spectacular and falls on flavor,” he says.

While the restaurant may be a beacon for fine dining, Chef Keller prefers not to think of The French Laundry as a bastion of innovation.

“Innovation doesn’t really play a big part in what we’re doing. We learn as we go. We evolve as we go. What we want to do is nourish our guests, and in the same way, nourish ourselves,” Keller says.

On the wall near the Pass at The French Laundry is an embossed quote from Chef Keller’s 1999 cookbook:

“When you acknowledge, as you must, that there is no such thing as perfect food, only the idea of it, then the real purpose of striving toward perfection becomes clear: to make people happy. That is what cooking is all about.”

It is Keller’s ability to continuously tap into the idea of food as a means to happiness, and cultivating this same single-minded focus within his teams, that has given his restaurants such continued significance.

Throughout his career, he’s shown how much he values his role as a bridge between past and future. Alumni of his restaurants hold prominent positions across the culinary world. Two of his former team members, Grant Achatz and Corey Lee, have gone on to earn three Michelin Stars at restaurants of their own, with Keller’s full blessing and support.

“Our profession is this profession of generations—generations built upon generations,” Keller says. “We stand on the shoulders of those who came before us.”

A legend in his own right, passing into the next chapter. And he’s not finished yet.

“Our job is to give each of us—even the youngest people in our restaurant—the

confidence and the courage to stand up for themselves.”